Advocacy

What is advocacy?

There are many definitions of advocacy. The Princeton Net defines advocacy as active support of an idea or cause, particularly the act of pleading or arguing for something. UNICEF states that "Advocacy originates from advocare, ‘call to one’s aid’ or to speak out on behalf of someone, as a legal counsellor. Conceptually, advocacy fits into a range of activities that include organizing, lobbying and campaigning".

Based on our experiences in ASPBAE, advocacy means influencing and transforming mindsets, practices, and policies at different levels towards the promotion of human rights. ASPBAE gauges the impact of its advocacy by looking at the 3Ps, which include..

- Policy - Are there new policies passed or amended that support the right to education?

- Process - Have decision-making processes been changed to enable civil society, especially the marginalised sectors, to participate? Is there a shift in power relations in terms of the governance of education?

- Public awareness - Have people/communities changed their views in favour of education? Have they joined the advocacy to demand their right to education?

Policy

Policy Process

Process Public Awareness

Public Awareness

Advocacy involves different strategies that include lobbying to influence the decisions of power-holders, mobilisation and awareness-raising to seek support from the community on issues and community research to generate recommendations based on the realities of the people.

An ‘action’ is an important and non-negotiable aspect of participatory action research. Once the research group has gathered data, analysed it, and arrived at findings and recommendations, it is necessary to steer action. The action here particularly refers to creating awareness about social issues and influencing decision-makers to implement research recommendations. Sharing findings with a large group of people, communities, and policymakers is a crucial first step to initiate dialogue and deliberations regarding the emergent issues and exploring possible solutions for the problem. Other activities like publishing research papers, holding local community events, launching media campaigns, meetings with government representatives, among other actions, are equally significant.

Since it is a participatory and collective process, it is important to involve all the stakeholders in the knowledge dissemination and advocacy process. Joint planning, reflection, and action are expected to happen throughout the process.

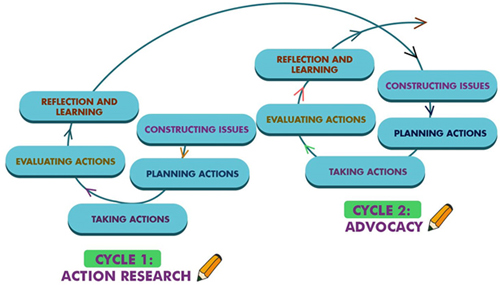

Cyclic process of action research and advocacy.

Source: From Action Research to Advocacy

(Praxis Note 71), INTRAC 2015

Action research is a cyclical (spiral) process and follows the action-reflection-action model. This means, a group of researchers constantly reflects on their decisions, actions, and learning. This evaluation process ensures their actions are appropriate and relevant to their environment.

An 'action' is an important and non-negotiable aspect of participatory action research. Once the research group has gathered data, analysed it and arrived at findings and recommendations, it is necessary to steer action. The action here particularly refers to creating awareness about social issues and influencing decision-makers to implement research recommendations. Sharing findings with a large group of people, communities, and policymakers is a crucial first step to initiate dialogue and deliberations regarding the emergent issues and exploring possible solutions for the problem. Other activities like publishing research papers, holding local community events, launching media campaigns, meetings with government representatives, among other actions, are equally significant.

Action research is a cyclical (spiral) process and follows the action-reflection-action model. This means, a group of researchers constantly reflects on their decisions, actions, and learning. This evaluation process ensures their actions are appropriate and relevant to their environment.

As you can see in the graph, advocacy and research are interlinked and cyclical. However, in our experience of YAR, we realised that it is rare to witness such clear and linear cycles. In fact, in reality, the cycles are messier and overlapping. For instance, advocacy at home and in the villages began much before the research project. Young girls and women had to convince their families to be part of the YAR project. Negotiating gender roles at home/community and supporting other friends in doing so was the first step for these researchers.

- Doing research requires valour

We observed, most of the YAR project partners were already negotiating and advocating in their own homes simultaneously alongside conducting the research. Adolescent girls and young women had to convince their families to be part of such research projects along with seeking permission from the community and local government representative members. This required a lot of advocacy skills and great courage. In succeeding stages, the youth researchers themselves started encouraging other young people to participate in the dialogues or interviews of their research process. After the data had been collected and analysed, substantive advocacy followed, including presenting the findings to large audiences, creating campaigns, etc.

Action research is a challenging endeavour. The young women and men experienced apathy, bullying, and sarcasm from their neighbours while doing research (in Nepal, the youth researchers were even chased by drunk men). It requires valour to continue their research despite facing these challenges.

- Actions can emerge at any time during the research

One of the significant features of action research is that action is always embedded in the process. Since the research is done by the community and for the community, the process becomes empowering for the people involved in it. In YAR’s experience, it was evident that the individuals and teams were empowered as a part of the process and they started making informed choices in their daily personal and social life.

The young women researchers from remote villages of the Nashik district of India began to investigate gender discrimination in educational opportunities in their communities. Very soon, the group realised that the girls in their villages (including themselves) do not have a non-threatening and comfortable space where they can talk about their own experiences. Not even in their homes!

Many of the girls were confined to the home and to the household activities which had not led to an awareness that they lacked such a space. However, girls felt a strong desire to have their own space for research work where they could gather, share and work comfortably without pressure/disturbance from anyone. The group came up with the idea of a village library- which was named as the Shodhini library (Shodhini means woman/girl seeker). Because the library was run by researchers themselves, it helped to build ownership and solidarity among the group. The library was further also used as a safe and comfortable space for conducting interviews, which in turn not only empowered the girls but also enriched the data collection process.

The group did not wait for the action to happen at the end of completion of the research but the actions were seamlessly integrated into their research process itself. These examples highlight that the process of action research is neither linear nor neatly structured. Each project has its unique needs, and therefore one has to respond to the emerging situation on the ground. The examples also provided greater understanding of advocacy and actions.

Evidence-based dissemination and advocacy are essential steps of action research. Arriving at an action plan after analysing social issues and raising consciousness about social, economic and political situations is the primary goal of the youth-led action research.

Collective action and advocacy are important in this process. Key findings should be shared among all relevant community groups, including those who have supported/collaborated in research work, people who may be affected by new practices and programs, or people who can implement the findings on the ground.

Wilson et al. (2010) have captivatingly defined dissemination as “a planned process that involves consideration of target audiences and the settings in which research findings are to be received and, where appropriate, communicating and interacting with wider policy and…service audiences in ways that will facilitate research uptake in decision-making processes and practice.” This means sharing (dissemination) of research findings is a systematic process that encompasses careful planning, thinking of target audiences, avenues, and methods to communicate with your focused group of people.

It is important to identify all major stakeholders who are involved in the project and who may benefit from our research work. Field practitioners, social activists, and policy advocates are the ideal group for beginning our discussion and dissemination work. Because they are not only knowledgeable about our research topic but also can understand all nuances of the research study. Hence, engaging them in a dialogue to co-produce strategies for action and advocacy is a great idea.

Effective planning and preparation can make this process smooth and effective for all the stakeholders. A carefully drafted plan and thorough preparation can save lots of time, resources, and energy. Collaborative communication and open sharing of research findings can speed up the advocacy phase.

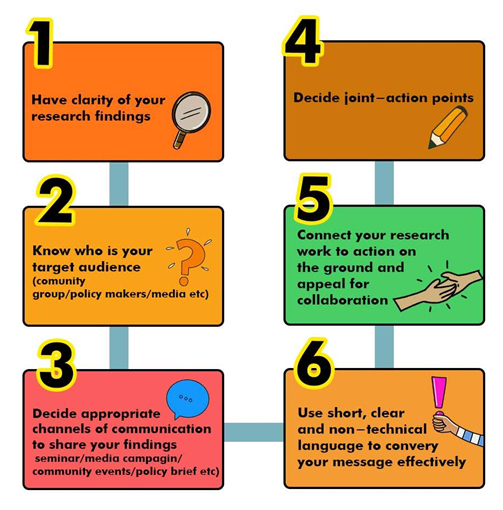

So, how do we disseminate our research? A suggested toolkit:

From ASPBAE's experiences of undertaking and supporting YAR in different geographical contexts, the following activities were carried out by our member organisations in their respective communities. Please note that this is a suggested list and one needs to adapt activities according to one’s environment.

So, how do we disseminate our research? A suggested toolkit:

From ASPBAE's experiences of undertaking and supporting YAR in different geographical contexts, the following activities were carried out by our partner organisations in their respective communities. Please note that this is a suggestive list and one needs to adapt activities according to one’s environment.

- Dissemination of YAR findings and recommendations:

Sonali presenting research work at the village assembly

Sonali presenting research work at the village assembly Once the research draft is ready to be shared with partners, it is important to start planning and organising dissemination events. The objective of such events is to share research findings with relevant groups who can benefit from updated knowledge and shape their practices in the field. Organising small events at the community, organisational and block levels is the best way to kick-start this.

The Shodhinis presented their research findings to the gram panchayat (village-level decision-making body) and initiated a dialogue between decision-makers (mostly elderly men who are often reluctant to listen to young girls and women’s voices), community members, and girls from the villages. This was very effective because this activity not only boosted the confidence of young researchers but also opened up spaces for marginal voices to come to the centre.

People from the development sector who are dealing with community issues are another brilliant group to engage with. They not only have a great influence on the community but can also contribute to the work.

Example: A full-day meeting with field practitioners, community workers, and development professionals was organised to advocate for the action research tool as an intervention for the marginalised communities. 37 diverse partners participated in this. This meeting was instrumental in forming a network and learning community to share and learn more about action research methods and guide their work with marginalised communities. The meeting concluded with concrete three action points.

Presenting the research work at national and international conferences and discussing the topic, methods, and findings with peer NGOs and academics is a fantastic way to connect theory to practice. One has to constantly look for such spaces, write to people and keep them informing about the current work. Subscribing to journals, websites, and other online groups will help in this.

Example: A full-day meeting with field practitioners, community workers, and development professionals was organised to advocate for the action research tool as an intervention for the marginalised communities. 37 diverse partners participated in this. This meeting was instrumental in forming a network and learning community to share and learn more about action research methods and guide their work with marginalised communities. The meeting concluded with concrete three action points.

Presenting your research work at national and international conferences and discussing the topic, methods, and findings with peer NGOs and academics is a fantastic way to connect theory to practice. One has to constantly look for such spaces, write to people and keep them informing about your current work. Subscribing to journals, websites, and other online groups will help in this.

- Workshop on drafting research-based recommendations

A collective workshop for articulating research-based recommendations can be organised. It is essential to put together a list of recommendations as well as identify target groups that can be approached.

A group of young researchers can come together for drafting recommendations in a creative format. Writing recommendations and making appropriate demands in crisp and clear words is necessary, especially when dealing with government authorities.

A group of young women researchers from rural India came up with a Girls’ Charter for Education. Beautifully designed bookmarks, flyers, and posters that complement the content were created and made a positive impact.

- Youth camps

Young people have immense potential. Only through providing a safe, participatory, encouraging, and conducive learning environment can this potential be nurtured. Youth camps can serve as a platform for sharing research findings and equipping young people with the knowledge and skills to take positive actions in their personal and social life. Choosing an appropriate venue, creating a flexible session design, and allotting enough time to listen to young people’s stories are all important elements of a youth camp.

YAR partners from the Philippines organised a youth camp on education where young people from the community were engaged. Such avenues provided an opportunity for youth to engage in dialogue and voice out their concerns. After educating them about action research methods, youth were encouraged through participatory activities and discussions to share their community challenges and come up with ideas to tackle those problems together.

- Validation process - a key activity in the YAR

Meeting key stakeholders:

Meeting key stakeholders

Meeting key stakeholdersArranging meetings with government officials and other influential individuals is crucial to propose recommendations and influence their decision-making. Given the challenges associated with finding time amid their busy schedules, it is important to plan and seek relevant approvals beforehand. The event must be short, participatory, and arranged at a convenient time and place for all the participants. Remember to print appropriate handouts, flyers, and other information for sharing with participants and the press.

For instance, in 2017, YAR partners in the Philippines organised such meetings with the mayor, police, officials from the Department of Education and Department of Social Welfare and Development, parents, and community members in Capul island, Samar. The group of young women researchers presented the key findings and asked the participants to validate them. The researchers used creative methods to validate their findings by engaging with the audience.

The meeting concluded with a concrete action agenda and commitments by the government officials to look into urgent demands raised by the research findings and discussion. The idea of establishing a community learning hub was agreed upon by all the members.

Youth camp in FGD, Indonesia

Youth camp in FGD, IndonesiaYouth camp validation:

A creative way to validate research findings is to arrange a focus group discussion with relevant representatives from similar contexts. In the case of Indonesia, young women researchers from marginalised backgrounds were consulted about their experiences to draw parallels with the study findings. The meeting was a reflective experience for the participants and proved to be helpful in the validation of the research findings. The discussion also helped strengthen the scale and scope of their research.

- Advocacy events with different stakeholders

A key component of undertaking action research is to engage and collaborate with different key stakeholders to pave the way forward. These stakeholders ought to be carefully identified in order to address the different key objectives of your research, which could include information dissemination, building community ownership, filling institutional gaps, or facilitating policy advocacy, among others.

Manisha presenting the results of the YAR and their

Manisha presenting the results of the YAR and their recommendations on education during a session on

education inclusion during the 4th Asia Pacific Meeting

on Education in Bangkok.

In 2017, on the occasion of the International Day of the Girl Child on October 11, a public programme was organised by the Shodhini Team to advocate for the recommendations made by young women researchers. The event was conceptualised, planned, and hosted by the young researchers themselves. Important stakeholders, including representatives from the local government departments were invited to the programme. Block development officers, education department district heads along with other government officials participated in the programme. In this meeting, the Girls’ Charter was presented and handed over to the guests. The Charter listed the girls’ recommendations and demands for making quality education accessible to everyone. This programme was highly successful, as many stakeholders publicly committed their support.

Taking the youth voices to broader advocacy and civil society platforms:

It is often contradictory that in the spaces where youth-related agenda and work are discussed, youth representation is severely lacking. There is a need to continuously create and keep seeking spaces where youth can voice their opinions and contribute to the dialogue which is significant for their future. This requires advocacy and networking skills for negotiating a platform for youth where they can represent their communities and share their research work. On the other hand, there is also need to mentor and coach the youth groups so that they can effectively utilise the opportunity to share their findings and recommendations with a diverse and highly influential network at various platforms.

Several Shodhinis from India travelled to the Philippines to participate in a workshop organised by SEAMEO Innotech’s ‘15th International Conference on Inclusive Education’ where their story of being young researchers and their research work was featured.

The ASPBAE regional meeting of YAR partners held in Chiangmai in August 2017 was successful in this regard. The YAR team was invited to this meeting to share their findings, exchange lessons, and strengthen the action-reflection process. It was an empowering process for the young women from three countries who, for the first time, travelled to the new country and interacted with people and organisations from other countries. Their participation in the meeting was useful in building the regional agenda on education, skills development, and the empowerment of marginalised young women in the region.

The regional meeting held in Chiangmai in August 2017 was successful in this regard. The YAR team were invited to this meeting to share their findings, exchange lessons, and strengthen the action-reflection process. It was an empowering process for the young women from three countries who, for the first time, travelled to the new country and interacted with people and organisations. Their participation in the meeting was useful for building the Asia agenda on education, skills development, and the empowerment of marginalised young women in the region.

- Actions can emerge any time during the research

One of the significant features of action research is that action is always embedded in the process. Since the research is done by the community and for the community, the process becomes empowering for the people involved in it. In YAR’s experience, it was evident that the individuals and teams were empowered as part of the process and they started making informed choices in their daily personal and social life.

In Indonesia, ASPPUK and NEW Indonesia through the LP2M project came up with the idea of a shared community learning centre (CLC). Through this CLC, youth groups aim to facilitate life skills education and women empowerment activities.

Mai-Mai with her daughter by her side facilitating

Mai-Mai with her daughter by her side facilitating a meeting with the community on issues of solo parents.

Mai-Mai, a young woman researcher from an urban poor community in the Philippines writes about the story of single parents taking action.

When our organisation, Youth for Nationalism and Democracy (YND) became a partner of ENet Philippines in the YAR Project, I participated in the project. I was the team leader for our area in Quezon City where the YAR was conducted. While involved in the project, I came across young women and men in my own community who share the same background and circumstance – stricken by poverty, young parents, solo parents, were not able to finish formal schooling but still hold on to a dream of having an education. Most of the young women and men who freely shared their stories for the YAR are solo parents. YND thought of organizing them. We consulted these young solo parents regularly and with them, we planned for the formation of a Solo Parent Organisation in our community in Bagbag. We were able to form our Solo Parent Organisation mostly made up of the young women and men who participated in the YAR. We conducted education among ourselves on our rights as solo parents as provided under the Solo Parent Act. We found out that many of the provisions in the law are not being implemented, we found out that we have rights as solo parents – pursuing these became the basis of our plan of action and activities. Until now, we are active in our community and we continue to hold seminars for our members while we continue to recruit new members. Presently, we are pursuing to have a center “Arugaan” for our young children while we pursue alternative education and livelihood. We know that challenges and barriers continue to exist so while we continue to consolidate our organisation, we also partner with the government, especially the local government, non-governmental organisations among others, to help us in our plans. We are doing a lot of education work, through the help and guidance of YND, not only on solo parent issues but also on other issues in our society which affect our lives and communities.