WHAT ARE THE WORKSHOPS?

In this section, you will learn:

1. The YAR action research process

2. Facilitation and mentoring support required to be given by the practitioners to the youth

3. To facilitate the YAR inputting workshops in a participatory and youth-centric approach

4. General workshop design with country-specific variations

The YAR followed a process of facilitating the selected youth researchers to conduct the action research in their communities through intensive workshops and hands-on mentoring during the field research. The workshops were designed to provide inputs on research skills such as creating the research tools, data collection, data analysis, critical thinking, and documentation. Along with a skill component, the workshops also provided the space to develop other competencies such as leadership, initiative-taking, teamwork, creativity, and problem-solving. Along with the research input workshops, each partner conducted various and context-specific sessions to build the researchers' perspectives on gender, education, and social justice.

In this e Manual, we have created a replicable module for all the research input workshops, as well as some of the perspective building sessions. Each of the modules follows the general design we had in mind while designing the workshops, but in practice, the workshops had variations incorporated by the ASPBAE members. Notes about these variations have been added to the general modules.

APPROACH

The workshop follows the spirit of the YAR in its approach and pedagogy. As this is a youth-led action research, the workshop design also, reflects this commitment to youth leadership, and initiative. The workshops have been designed to be participatory, experiential and transformative. This means that:

- The workshops do not believe in a teacher-student dichotomy, and instead create a learning environment where everyone, including the facilitators, are co-learners

- The youth participants are actively involved in the workshop and not just passive listeners

- The youth participants have the freedom to question, challenge, and voice their opinions and doubts – the workshop follows a dialogue-based pedagogy

- The workshops should give importance to the lived experiences of the youth participants and encourage them to share these experiences and reflect on them to deepen their perspectives

- The workshops create a safe and nurturing environment for the youth participants to share sensitive matters and learn to respect each other despite their differences

- The workshops will only be transformative when there is an engagement of our heads, hearts, and hands. Hence, most of the sessions in the workshops are based on a psycho-emotive approach that engages the participants at three levels - the cognitive, the emotional, and the corporeal.

To follow this youth-friendly approach of the workshops and facilitation, ASPBAE has identified certain non-negotiable dimensions. These are:

- The workshops should be residential, in a safe and comfortable environment

- They should be for four to five days

- The number of participants should be not less than 20 and not more than 30

The workshop facilitation team plays different roles. Each role has its responsibilities and essential qualities and skills. Following is a table that gives more information about the various roles in a facilitation team. Please note that while a person can play more than one role, it would be virtually impossible for only one person to do everything. Hence, a team of facilitators is very important and needs to be groomed from the beginning.

Role |

Responsibilities |

Skills/Qualities required |

Lead facilitator |

|

|

Group facilitators |

|

|

Logistics |

|

|

Mobilisation and participant liaison |

|

|

Subject knowledge experts |

|

|

Documentation – photo, video, written |

|

|

MODULES

The following workshops are designed to train young researchers to conduct action research in their local communities. There are two types of workshops: a core set of workshops designed to build research skills, and a supplementary set designed to develop skills and perspectives in gender, education, and youth leadership.

- Understanding the concepts, steps, and ethics of action research

- Developing the tools for the action research

- Doing short research and analytical exercises as research practice

- Developing leadership, self-efficacy, and teamwork skills

- How to compile and organise collected data meaningfully

- How to draw analyses based on the data

- How to think critically about data

- How to describe the data and compile reports from the findings

- How to draft recommendations and demands based on the findings

- Learning about patriarchy, poverty and powerlessness as the interconnected structures causing gender discrimination

- Becoming aware of discrimination based on gender in one's own life

- Learning about our bodies, reproductive systems, and safe sexuality

- Learning to become role models in one's community

- Developing confidence to make one's voice heard in the family, among peers, in the community, and other civil society platforms

- Learning strategies to challenge patriarchy at the personal as well as collective level

- Learning to combat gender-based violence

- Mentoring

- Learning more about one's local community

- Appreciative inquiry model – appreciating the nurturing aspects as well as analysing the hindering factors of the community

- Making actual maps of the community as a hands-on approach to understand the local geography and social realities

The modules are written in a way that ensures they are easy to understand and replicate. Each module begins with a list of stated objectives or intentions of the workshop. There is also a section containing preparatory notes for facilitators. All workshops are divided into sessions that fulfil a particular objective of the workshop. Each session in the module will contain the following information:

- Time required: The estimated duration of each session

- Resources required: Materials that are needed in the session

- Main activities: Exercises, games, or presentations which constitute the main part of the session

- Discussion points and questions: To take forward the learnings from the activity

- Facilitation notes: Things to consider for facilitators

- Expected outcomes: What to expect at the end of each session

WORKSHOP 1 – UNDERSTANDING ACTION RESEARCH

- To understand the framework of the action research and its relevance to the participants' lives

- To motivate participants to undertake the action research in their communities and articulate issues and actions on the chosen issue

- To develop conceptual clarity on participatory action research and its various features, steps, and processes. Further, to develop clarity on the ethics of research

- To agree on a program framework/design and action plan to implement action research in their communities

- To deepen perspectives on gender and education

- To build the confidence of and rapport amongst the participants to work with each other and share ways of working both as individuals and as a collective

- Preparing the space: Since this is the first workshop with the participants, it should be noted that, it may be the first time for many participants in a number of contexts to step out of their homes and be in completely unknown surroundings, away from their family for such a length of time. Hence, ensure that the living and learning spaces are nurturing and comfortable for the participants. Make sure the learning space is not too formal and intimidating, A circular seating arrangement works better. Further care should be taken to be sensitive to their food habits, meal and sleep timings, and giving ample time for fun and games. These allow the participants to grow comfortable and participate more freely in the workshops.

- Research kit: In the YAR, each participant was given a 'research kit' at the beginning of the first workshop. This included a bag containing a notebook, pencils and pens, eraser and sharpener, a colouring box (crayons or sketch pens), and some easy-to-read books on the subject of the action research. These research kits need to be assembled before the workshops and given to the participants at the time of registration.

- Approach of the workshop: The first workshop is introductory, and focuses on developing the participants' skills as well as an understanding of action research. Hence, the workshop should be conducted in an informal and participant-centric way, making it a safe space for the youth to become comfortable as well as feel a sense of ownership to the learning process. Since the youth participants are from marginalised communities, it is also important to conduct the workshop in an appreciative inquiry approach. An appreciative inquiry model is a strengths-based approach that deliberately asks positive questions to ignite constructive dialogue and inspired action. Hence in the workshop, emphasis is given on to the youth's voices and needs. Youth participants should be encouraged to share their stories and even experiences of hardship and struggle must not be looked at with pity but celebrated as resilience-building endeavours.

- Baseline forms: At the beginning of this workshop, the participants should be asked to fill a form that collects their 'baseline' data and helps create a baseline for the organisation to design and formulate interventions in the action research process. A sample baseline questionnaire is given in the downloads. It includes questions about demographic data along with specific questions related to gender awareness, mobility, negotiation skills, educational aspirations, and health awareness. Once the baseline data is collected from the participants, it can be used together with the 'endline' data (collected at the end of the action research) as an important indicator of the self-transformations in the participants during the action research.

Activity

![]()

Welcome the participants to the workshop by saying a few warm words of welcome. Many participants may have found it challenging even to come to the workshop (getting a leave, reluctant parents, etc.) so talk about these and praise the participants' efforts to join in the action research process.

Conduct a small ice-breaker to make the participants comfortable and relaxed. Now, tell the participants that we are going to introduce ourselves to each other in a fun and interactive way. Each participant is given a blank name tag. Ask the participants to think of a positive adjective for themselves, which begins with the same letter as their name. The adjective can be in any language. Eg: Adventurous Anita, Compassionate Cecilia, Marvellous Maria. They have to write their names and adjectives on the name-tag and announce it to everyone else. They can also briefly say why they chose that particular adjective for themselves.

Things to consider :Some participants may take longer to warm up and may not participate fully in the beginning. For certain activities like this one, it is okay to give a gentle push to such a participant. For example, suggest a few adjectives they would like to use and engage in further dialogue about it. If the participant continues to be unwilling, let them be. Do not insist on their participation, or call other people's attention on them.

Activity

After the participants have introduced themselves, ask them to share what they think is the purpose of the workshop. Ask 2-3 participants to speak. Taking forward from there, write the words on the board and ask the participants if they have ever heard of research. Ask them questions such as:

1. When you think of research what is the first thing that comes to your mind?

2. Who usually does research?

3. Where does research usually take place?

Participants will usually answer that research is done in labs, by scientists, educated people, etc. Counter this with a statement, that according to you, everyone is constantly doing research. We are all researchers. Ask the participants, can you think of something you have 'researched' in your life? Research is finding information in a systematic way to a specific question. You may have researched colleges, courses, jobs, places to go, food, recipes, even people! Ask the participants to give examples of something they have 'researched'.

Now, tell the participants that this workshop is to develop our research skills so that we can do research and unearth new information from our communities and our lives. Further, this is not just research, it is action research, because we are not only going to discover information but also use it to bring about positive changes in our lives and community.

What kind of changes? This will be answered through an exercise.

![]()

Ask the participants to trace the outline of their hand on a piece of paper. This is a representation of themselves – each hand is as unique as each participant in the room! Ask the participants to look at each other's 'hands' and appreciate their differences as well as similarities. Draw your hand on a board or larger paper. Tell the participants that what looks like a hand is going to become something different. Now, draw a beak and an eye on the thumb and feet at the base of the hand. This transforms the hand into a bird in flight. Ask the participants to make their hand into a bird as well.

After all the participants have drawn their hand-bird, ask them to pin up their drawing on a notice board so that it looks like many birds are taking flight.

Discussion points :

Tell the participants that the hand to bird exercise is a metaphor for the self-transformation they will undergo during the workshop, and more generally in the action research. The workshop will enable them to gain a vision (eye), voice (beak), wings (confidence), and an understanding of the context (feet). Just by adding a few elements to the hand, it has the potential to become a bird. Yet the hand remains as it is. And so similarly, the participants will still be themselves, and yet gain some important tools to do and be so much more.

This exercise should help the participants become more grounded in the objectives of the workshop. It will help prepare and excite them for the next sessions.

Activity

In this exercise, the participants will deepen an understanding of their communities. Depending on the number of participants, make groups of 5-7 participants from the same community. Give them a chart-paper and ask them to discuss and write their responses to the following questions:

1. What are the special features of their community?

2. What factors in their community are nurturing/conducive to their (the participants') development?

3. What factors in their community are hindering their (the participants') development?

Ask the participants to draw a rough map of their communities showing the features they have mentioned (if possible) as well as the important landmarks.

Discussion points:After the participants have finished, ask each group to present their responses and map to the entire group. Encourage people in the audience to ask questions, dig for more information. Ask the presenting groups questions about why they feel a certain factor is hindering/nurturing.

After all the groups have presented, hang their chart-papers for everyone to see and ask the participants to glance at all the presentations once again. Do they see any commonalities? Is something repeated – especially among the nurturing/hindering factors? Does anything particular stand out?

Ask the participants why certain factors are common across different geographic/social/cultural communities. Do they think these are true for other communities too? Eg – would a hindering factor for a rural community apply to an urban area as well? Invite the participants to share their opinions.

Finally, address the question that many participants will have by now – why are some factors common across various communities? What are the real causes behind the hindrances that marginalised youth face in today's world? End the discussion by stating that this is just the beginning, but raising questions is important at the beginning of action research. Soon, the participants will endeavour to find the answers, but for now, it is very good that they have started asking questions and making connections.

Expected outcomes:This exercise should help the participants become more aware of their local context and analyse them in terms of how conducive it is to their development. It will also enable the youth participants to find common ground with each other and prepare them for a broader understanding of structures in the next session.

Activity

This is a psycho-emotive exercise that helps participants to understand the structural roots of the marginalisation and discrimination they may face in their lives. Before beginning the activity, tell the participants that this is a serious exercise that requires introspection and sharing. It may also cause people to feel emotional and vulnerable. Hence together we need to create a safe space for people to express themselves openly. Discuss the principles required to create a safe space with the participants. Some principles can be:

- Full attention – when any participant speaks, everyone else listens attentively, without interruptions or parallel discussions. If anyone has questions, they should be addressed once the speaker has finished.

- Respecting others' privacy – if any participant has shared private or sensitive information, others will respect his/her privacy and not talk about it outside of the session, to the person concerned, or anyone else.

- No judgement – we are in a non-judgemental space. Even if you may disagree with someone else's belief or action, they are free to believe/act on it. Do not judge that person and/or gossip about them with others. If you wish to have a dialogue about your disagreement, ask for that person's time outside of the workshop sessions.

- Punctuality – sessions will begin and end at times that are agreed upon. The group will not wait for latecomers.

Ask the participants if they agree with all the principles. Each principle should be agreed upon and 'vowed' by all the participants and facilitators. Ask the participants if they would like to suggest any more rules for the space. Once all the principles are agreed upon, tell the participants that we have now officially 'sealed' the space as a safe one.

Following this, the participants will become more serious and focused on the next activities.

![]()

First, divide the participants into pairs, and ask them to pair up with someone they do not know well. Once the pairs are ready, ask them to sit back-to-back, looking away from one another but supporting each other with their backs. Tell them that the first part of this exercise is silent and requires only introspection. But since we are all together, it is important to support each other in non-verbal ways as well, which is why the partners.

Then, give each participant a piece of paper and a pen/pencil. Get them to think of their mothers or important mother-figures in their lives. How does she look? What would she be doing right now? Ask the participants to hold their mothers/mother figures in their thoughts. Then, ask them to write the following three things:

1. Mother's name

2. One quality you admire in her

3. One opportunity that you think she would have benefitted from, but which she couldn't access

After the participants have finished writing, ask each of them to stand up and read aloud the three things they have written about their mother.

Discussion points:As the participants begin talking about their mothers, a pattern will emerge, as many mothers' stories will be similar, especially the lack of opportunities in education, careers, and exercising personal agency. The participants should also begin noticing these patterns. If not, bring their attention to it by asking, what are some of the commonalities we noticed about our mothers' stories?

Some participants may get emotionally charged while talking about their mothers. Encourage them to continue talking and tell the group it is okay to cry and express difficult emotions as it is a form of catharsis.

As the participants are talking about the common aspects of their mothers' stories, make a list of these on the board. Continue the discussion by asking the following questions:

1. Why do you think there are so many commonalities?

2. Do these commonalities cut across geographic and socio-economic backgrounds as well?

3. Do these commonalities transcend age? Do you think the opportunities your mother was denied, are you (or your sister/friend) also denied?

4. Are such opportunities denied to women and girls only, or to men and boys as well?

5. What opportunities are denied to women and girls only? And why?

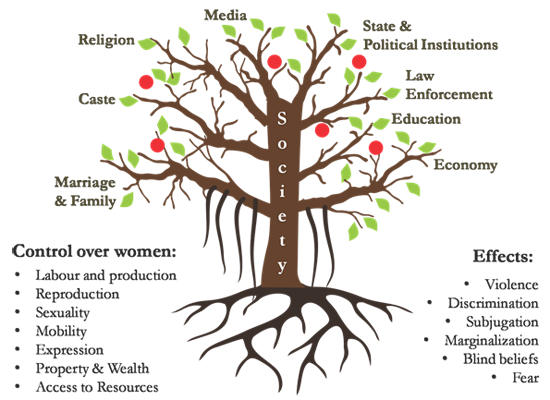

The participants will realise that many opportunities are only denied or restricted to women and girls. These restrictions are common to women and girls across different locations but are faced more severely by those who are also deprived financially or socially. Eg – women's education is not encouraged in various classes in society, but for families living on the brink of poverty, it is easier to invest in the education of their sons, as girls and women are not regarded as the family breadwinners. Hence, it is a combination of poverty, patriarchy (the belief that men/boys are superior to women/girls), and powerlessness that enmeshes the lives of all women and girls, resulting in restrictions upon their mobility and denial of opportunities for their growth and development.

At this, draw a triangle on the board and label its three points as Patriarchy, Poverty, and Powerlessness. Explain that this triangle of three 'P's together create a stronghold of restrictions, denials, discrimination, and violence over the girls' lives. Ask the participants to share instances and examples of how they think this 'Permuda' triangle operates in their lives. Encourage them to share stories from their lived experiences.

Finally, conclude the activity by thanking all the participants for having the courage to be vulnerable and share stories of hardships. But the important realisation is that these problems are not personal but rather social, affecting all of us. Hence, we need to come up with collective solutions to break the stronghold of this triangle. This is what we are going to endeavour to do, in this workshop, as well as throughout the action research. But the first step to challenge any stronghold of power is to become aware of it and understand it thoroughly.

Expected outcomes:This exercise should help the participants become aware of the social and structural roots of their problems. It will provide a broad understanding of gender oppression and its interlinked causes. It will also help them focus on the research objectives, one of which is more gender parity.

The session on understanding research is a series of smaller activities, discussions, and group work that can be customised as per the participant groups. The objective of this session is three-fold – the participants should understand the concept of action research, the steps involved in action research, and the ethics of action research.

The various activities and information to be provided are given below.

Activity

This activity aims to give the participants a simple but clear conceptual understanding of action research. To begin, distribute meta cards to the participants and ask them to write or draw anything that answers the question, 'What is action research?' After this, ask the participants to show and share their responses with the group.

After the participants have finished, explain to the participants that research is nothing but a systematic and disciplined search for new information or knowledge. However, we take this definition forward by asking, what kind of knowledge are we looking for? And who will undertake that search and unearth new knowledge? Action research believes that everyone has the right and the potential to become a researcher and create knowledge. It upholds that the most powerful form of research happens when it is done by the people upon themselves. Hence, young people are best equipped to research on youth. Or rural girls, even if they are still in school, or have dropped out, are still the best people to research and create knowledge on rural girls. No research expert can match the expertise that comes from actual lived experience. Hence, action research believes that the researcher and the researched should be the same.

Discussion points:The following points will help to explain and clarify the concept and principles of action research.

Features of action research:

- A unique kind of research which is done by the people upon themselves, on issues that are central to their lives

- Collective discussion and community action are central to action research

- The goal of action research is transformative – ie to transform one's life and one's community

- Action research is not only about understanding the problem but also requires analyzing the root cause of the problem and taking effective action to alleviate or solve the problem

Principles of action research:

- People can only understand their life situations by learning from their own and each other’s experiences

- Commitment to working with people whose voices are not heard in the mainstream

- Belief in the people's wisdom and the right of all to create knowledge

Activity

Since research is a systematic process of inquiry, there are designated steps in its process. Knowledge of these steps is a must for any researcher. This activity suggests a fun way to provide information about these steps to the youth participants.

To begin with, tell the participants that they are going to play a game of treasure hunt where the participants, divided into groups, hunt for a series of clues that lead them to a treasure. The team that reaches the treasure first, wins it. The treasure can be a basket of small gifts, but make sure in the end all the participants get some gifts. After the exercise, ask the participants to list down the steps needed to find the treasure. Usually, (ADD COMMA) the participants will say that they were given the first clue, which they decoded, and which led to the next clue. This went on until they found the treasure.

Discussion points:Explain that action research follows a similar pattern of steps. We begin by identifying the research objective – the goal or 'treasure' of the research. But we don't know how to reach it! Hence, we need 'clues' or tools that will take us to our objective. These tools or 'research methods' are systematic and follow one another – not unlike the clues in a treasure hunt! You will not reach the treasure unless you systematically follow the clues.

Further, just as each clue requires you to take a particular action to move to the next one, in action research, the knowledge you unearth might also push you to take some action. This action can lead to further information, or the 'treasure' – the purported objective of your research!

For further clarity, these are the steps of action research:

1. Identifying the problem – generating the research question and research objective. Usually in action research, the objective is not limited to finding information or knowledge, it can also lead to concrete change or solution to the problem identified)

2. Finalising the methodology – creating the tools to collect data and analyse it

3. Collecting data – using the tools generated to collect information from the field

4. Assimilating and analysing the data – compiling the data, organising and cleaning it, and looking for meaning using critical thinking and dialogue

5. Taking actions – based on the data, taking individual or collective actions which will lead to a solution to the problem identified

6. Writing a report – documenting the research, writing the analyses, and drafting recommendations

7. More data collection or actions, if needed

8. Dissemination of findings – taking the research to various audiences and stakeholders, submitting demands and recommendations

Activity

In this activity, the participants are introduced to the ethics of doing research. This is a presentation-based activity; hence it might become lecture-like for some participants. If this happens, after explaining the ethics, organise the participants to enact small role-play by giving them situations in which they will need to go by a particular research ethic. Example situations are given below.

Discussion points:

Ethics of action research:

- Freedom - The respondent is an independent being and has the right to give or not give the information that is solicited

- Trust - Gaining respondents' trust is important, and making them trust the researcher is equally important

- Confidentiality – All information provided by the respondent should be kept confidential and, care needs to be taken to not allow it to fall into the wrong hands

- Respect – Respondents' opinions need to be respected

- Being just and fair- Considering all sides of the question and presenting an unbiased account of reality

Example situations for role play:

- Taking a girl's interview – asking for consent, if the girl finds a question inappropriate, how to communicate sensitive questions, what if she is reluctant to answer

- Asking the headmistress for permission to conduct a survey with schoolchildren – how to ask for permission, how to gain trust, be transparent

- Dealing with parents – responding to questions such as where this information will go, who will it benefit, why are you doing this, how much are they paying you, etc.

Activity

In this activity, the participants have to do an actual research as practice. Divide the participants into small groups (of not more than 4) and ask them to choose a topic on which they would like to conduct a small research study. The 'field' of the research should be limited to the campus only. But for example, they can research the lives of those who work on the campus, or the organisation (and the facilitators), or even on each other. Once they choose their topic, ask them what kind of research methods they will use.

The participants should design their questionnaires or any other data collection tools. After they have collected data, ask them to summarise the data and present it in chart-papers.

Discussion points:In the plenary, ask each group to present their research process and findings. Ask them to highlight the steps of this process, as well as the ethics they followed. Encourage other participants to also ask questions.

Expected outcomes:This exercise should help familiarise participants to the data collection process and make them comfortable and motivated to do research. It will also give the facilitation team a picture of how well the participants have understood the concept and process of action research and surface any doubts or questions in the participants' minds.

In the final session of the workshop, the participants and the facilitation team have to co-create data collection tools for the action research. A number of data collection tools should be pre-selected by the facilitation team. In the YAR, the following tools were used by the girls and young women researchers to collect data:

1. Detailed map of their village, hand-drawn by the girls, which indicated the village boundaries, roads and field, mark resources and facilities and showed the geographic distribution of various communities living in the village.

2. Census of girls aged 15 to 25 in their community. The census collected preliminary demographic data from 100 girls in each village.

3. In-depth survey with a sample of minimum 25 girls. The survey focussed on girls' experiences of and issues with the formal education system, as well as their learning aspirations, status at home, and menstrual health issues.

Activity

Explain to the participants that we have now arrived at the final leg of the workshop. Now, it is the participants who have to do most of the work. Motivate them to put all their energy into this research, as it is now theirs. Once all the participants express their enthusiasm, move to the next section.

Take the participants through the topic of the research as well as the research questions and objectives. Then explain to them that they must collect data about this topic from their local communities. This can be done in different ways, using various tools. Here, explains each data collection tool to them, and ask them what could be the best tool for their data collection.

When the tools have been agreed upon, ask the participants to design the tools. Eg. If the survey method is to be used, then ask the participants to make a list of questions which can be asked in the survey, and which will help us collect data that corresponds to our research questions. Divide the participants into groups (of 5-8 each) and ask each group to work on designing a different data collection tool. Each group has to then present their tool to the other groups and justify why a particular question is being asked.

Ask the workshop documentator to collect all the draft tools from the groups. After the workshop, the facilitation team should review the tools and use them to create a final set of data collection tools.

Facilitation notes:If possible, use the questionnaires or the tools generated by the participants to conduct a mock survey/interview. Ask a volunteer from the participants to conduct an interview with another participant using the tools generated. This will give the participants an idea of how to go about the fieldwork in their communities and familiarise them to questions they will ask in the actual data collection process. It will also help fine tune questions which are difficult to ask or comprehend.

Expected outcomes:This exercise should result in the first draft of the data collection tools such as questionnaires, interview guidelines, and survey forms. This will help familiarise participants to the data collection tools and the questions they will ask in the research.

WORKSHOP 2 – Research Analysis

The second workshop on action research focuses on collation and analysis of the data collected by the youth researchers. At the end of the workshop, the participants will be able to:

1. Reflect on the lessons learned in data collection

2. Review the integrity of the methods employed and whether ethics have been followed, and therefore ascertain whether the data gathered can be used

3. Tabulate the data into mastersheets and draw frequency tables and charts for further analysis

4. Generate first-level analysis and cross tabulation

5. Develop critical thinking skills and employ them in the data and map analysis

6. Analyse their maps through gender and social justice lenses

7. Identify and plan actions to take the action research forward

- Compilation of data: This workshop is organized a few months after the first workshop, once the participants have finished the data collection on the field. Hence, before the workshop, make sure the participants' data collection is complete. Ask the participants to put together the data they have collection (in the form of filled survey questionnaires, interview responses, or maps) and bring them to the workshop.

- Mastersheets: The first part of this workshop deals with compiling and organizing the data. If the data has been collected through a quantitative method such as a census or survey, the responses need to be inputted and organized into one sheet. These days, computer softwares such as Microsoft Excel have made it very easy to do this. However, marginalized youth may not always have access to computers. Hence, the compilation can be done manually, with the help of a 'mastersheet'. The mastersheet is in the form of a table with rows for filling in all the responses. (Link to an example mastersheet) – This example mastersheet is for a demographic 'census' of girls conducted by the youth researchers in India. The questions asked in the census (age, marital status, education, etc.) are reflected as column headings in the mastersheet, while the responses are tabulated in rows. Depending upon your research tools, you should create blank mastersheets in which the participants can key in their collected data.

- Group facilitators: If needed, each group of community researchers can be assigned a group facilitator to help in the data organising and analysis. As data analysis is a complex process involving various operations such as data tabulation, calculation, etc. the youth researchers might need help in the more technical tasks. Group facilitators can sit with the community groups for the entire workshop as the first point of contact and assistance in the workshop. Choose group facilitators from the existing facilitation team or invite external volunteers who have experience in research.

Activity

Welcome the participants to the workshop and ask them how they feel to be back in the learning space. Once a few participants have spoken, ask them if they are aware of the purpose of this particular workshop. Let a few participants respond before sharing the workshop objectives. The workshop will help the participants develop their analytical skills and enable them to meaningfully use the data they have collected. Data analysis will help in consolidating findings and building evidence for further actions and advocacy. Ask the participants to voice their doubts and questions about the purpose of the workshop.

At this stage, re-introduce the principles of the learning space to the participants and get them to discuss and agree to all the principles, or suggest any new ones. Some principles can be:

- Full attention – when any participant speaks, everyone else listens attentively, without interruptions or parallel discussions. If anyone has questions, they should be addressed once the speaker has finished.

- Respecting others' privacy – if any participant has shared private or sensitive information, others will respect his/her privacy and not talk about it outside of the session, to the person concerned, or anyone else.

- No judgement – we are in a non-judgemental space. Even if you may disagree with someone else's belief or action, they are free to believe/act on it. Do not judge that person and/or gossip about them with others. If you wish to have a dialogue about your disagreement, ask for that person's time outside of the workshop sessions.

- Punctuality – sessions will begin and end at times that are agreed upon. The group will not wait for latecomers.

Most of the participants should know each other since this is the second workshop. However, it's a good idea to do introductions as it will help the participants refamiliarize with one another, and in case there are any new additions. Introductions can be done with the help of a game, which will break the ice between the participants and make them more comfortable in the group. Given here are two introduction games, but different ones can be used as well.

Game 1:

Ask the participants to form a circle. Each participant has to take a step into the circle and shout out her/his name, along with an action, eg. a jump, a dance move. Once the participant finishes, the remaining participants repeat her/his name and action. Every participant in the circle gets a chance to do this.

Game 2:

Ask the participants to form a circle. Tell the participants, we are going to play a memory game. Begin by telling them your name. Now, ask the person on your left to continue. For this, she has to say your name as well as her own. Each subsequent person has to say the names of all the people before her, in the correct order. Anyone who misses or gets it wrong gets a 'punishment' and has to perform something for the audience.

Activity

Once the participants are familiarised and comfortable, invite them to reflect over their experiences of fieldwork and data collection. For this, divide the participants into small groups of 4 to 5. Groups can be random or according to location. Once the participants are seated in their groups, ask them to recollect the tasks they were given in the first workshop. These tasks were meant to be carried out in their local communities.

The tasks were:

1. Mapping the village (group work)

2. Census of girls (aged 14-25) in the village (group work)

a. Census form

3. In-depth survey of girls about their educational status and education needs for livelihood and life-skills (individually)

a. Survey questionnaire

Ask the participants to raise their hands if they have completed all these tasks. Congratulate the participants on completing the data collection.

Further, explain to them that the work they have done so far is called 'field work' or 'data collection' in research. It involves going to the field of the research, in this case, the local communities of the participants, and collecting data through various tools.

Now, ask the participants to discuss the following questions in their small groups, and based on their discussion, make a presentation that will be shared in front of the other groups.

1. What was your overall experience of the fieldwork?

2. During the fieldwork, what processes were easy and what was challenging?

3. How did you overcome the challenges?

4. How was the experience of working together as youth researchers?

Discussion points:

After all the groups have presented, ask the participants to voice out the common aspects of their experiences on the field, which emerged in the discussions. The common experiences that emerged during the YAR are given in the table below. Discussion points for facilitators are given in the next column.

| Participants' experiences | Facilitators' points |

| The creation of a new identity as 'researchers' for the youth. Girls, especially, who were earlier invisible and unacknowledged were now recognised in the village as leaders and change-makers. | Congratulate the participants for creating a new identity for themselves. This new identity challenges the traditional prescriptions of women as silent, meek, receptors of knowledge. |

| Discomfort around questions related to sexuality and menstruation. | This reflects our collective anxieties around women's sexuality. Why is this anxiety only around girls and not boys? It thrives due to patriarchal and sexist norms around marriage, especially the belief that women and girls are property that 'belong' to the men in their lives. If women start behaving according to their desires, they don't remain the meek, obedient objects that patriarchy expects them to be. That is why it is looked down upon, or feared for. |

| The voices and needs of the youth were brought to light through the research. | The YAR is a platform for youth to build rooted knowledge about their own experiences, opinions, and aspirations. This will help in recognising young people are a special group with their own needs and challenges, as well as take their voices to different audiences. |

| Through the research, the girls have also learned and demonstrated life skills such as effective communication skills, problem solving, how to convince people, etc. | It was important to speak to people who were different from us as it allowed us to look at the world through different lenses and broaden our thinking. |

| Difficulties and challenging to convince parents, family, and community members who are skeptical about the action research. | Acknowledge that doing anything new or unconventional is difficult and requires courage or 'valour'. But if we want to see the changes we have envisioned, then we must persevere. The process of change is slow, and requires steady, constant effort and stepping out of one's comfort zone. Even being assertive with our parents and negotiating with them to participate in the action research is an act of courage. Asked the participants to reflect on what happens when we show courage and take risks, especially in our own lives. Usually, there will be some opposition, which is what scares us. The threat of retaliation and backlash is what frightens us but not the act of courage itself. |

Activity

Explain to the participants that we are now going to begin the data analysis. But before the actual analysis takes place, we need to organise the data. This requires the following steps:

1. Checking the survey responses and eliminating incomplete responses

2. Coding the survey forms (in the YAR, an alphanumeric system was used to code forms corresponding to different communities, E.g. A1, A2… B1, B2, etc)

Ask the participants to complete the two steps in their community groups. The group facilitators can help the participants.

Once the responses have been coded, explain to the participants that these responses need to be compiled or put together into one sheet, so that they are easy to understand, and we can draw conclusions from reading them together. For example, each response tells us the story of one individual. But if we were to put all these responses together, then we have information that is representative of a larger population, say the youth of our community.

At this point, introduce the master sheets and explain how the master sheets have a table in which the data from the survey responses can be filled in. Ask the participants to check if the columns in the master sheet match the questions in the survey forms. Once the participants are familiarised with to the master sheets, ask them to fill the master sheets using the survey responses. Ask the group facilitators to help the participants and oversee the process, to make sure human errors are kept to the minimum.

Note about compilation:

If the data in the survey is quantitative, it can be given codes. For example, if a question in the survey is about the marital status of the respondent, then the potential responses can be:

Never married, Engaged, Civil partner, Married, Divorced, Separated, Widowed, Other. Each of these responses can be assigned a code, such as:

| Never married | 1 |

| Engaged | 2 |

| Civil partner | 3 |

| Married | 4 |

| Divorced | 5 |

| Separated | 6 |

| Widowed | 7 |

| Other | 0 |

While filling the master sheets, only the code corresponding to the response should be written. This will help make the compilation process simpler and less time-consuming.

Activity

After the participants have finished filling in the master sheets, congratulate them for completing a rather tedious process of data analysis. Usually, this task is given to professional researchers or done with the help of computers, but the participants have undertaken it themselves and done it so meticulously – which is in itself a huge achievement.

Once the data has been compiled, the next step is to calculate the number of responses. This gives us an idea of the trends in the research field. For example, if the survey is on education, calculating the number of responses to the question "Do you go to school/college?" will give us an idea of how many / what proportion of youth are enrolled in formal education.

Using the school question as an example, ask the participants to think about how they will calculate the number and proportion of youth that are school-going as well as those who are out of school, from the master sheet. Invite each group to come up with their own 'solution' to this question. Most groups will usually end up making a table like this:

| Education status | Number of youth |

| Enrolled | 148 |

| Dropped out | 265 |

| Total | 313 |

Most of the participants will have manually calculated the number of responses in each category. However, teach them to make frequency markers while counting as this will help make the calculation more accurate and avoid the chances of an error.

Explain to the participants that these are called 'frequency tables' as they show the frequency of responses for each question in our data. Once the participants understand the process of making frequency tables, ask them to make such tables for all the questions in the survey.

Discussion points:

Ask the participants what they can deduce about the education status of youth in their community from the frequency table on education status. What kind of a picture does it paint? Participants will answer that more youth in their community have dropped out from formal education than those who are in school. This is a dismal picture, as it means that either youth are not able to access education opportunities, or that they do not see education as a priority due to underlying factors such as poverty, discrimination, etc. Ask the participants to think about and write down such 'notes' for each table, answering the following questions:

1. What can you deduce about youth in your community based on this table?

2. What does this deduction tell you about the youth in your community?

3. What further questions come to your mind after looking at this table?

Activity

As the frequency tables only have numbers, ask the participants if numbers or frequencies are enough while talking about the trends or the big picture. Explain to the participants that it is easier to understand the proportion of youth to the total instead of using whole numbers. For example, instead of saying 25 out of 50 youth are unmarried, it is easier to say, half of the youth are unmarried. But how do you calculate the proportions? Ask the participants if they know any methods.

The best method to calculate proportional frequencies in data is through percentage. This is because, in percentage, all the data is standardised to 100. That is, 100 is used as a base and the frequency of data is calculated in proportion to 100. This makes it easier to understand and compare with different data. When we use percentages, we can compare the data from our community to bigger data – even national and international averages. For example, using the earlier frequency table on education status, if we were to calculate the percentage, it would look like this:

| Education status | Number of youth | In percent |

| Enrolled | 148 | 35.8% |

| Dropped out | 265 | 64.2% |

| Total | 413 | 100% |

This would tell us that 64% of our community youth do not go to school or college. We can compare this data with other data – we can find out the national and international figures and check how the youth in our community fare against national and international averages. If the total percent of out-of-school youth in the country is 45%, then it means that the youth in our community is worse off than the average youth in our country.

Once the participants have understood the concept of proportional representation in data and percentages, ask them to calculate the percentages for all the frequency tables.

Facilitation Notes:

If the participants are vulnerable or marginalised, a significant number of them will be out of school, or may not even possess the literacy and numeracy skills needed for such computation. However, that does not mean they be excluded from the process. Rather, more individual attention should be given to such participants so that they pick up the skills of numeracy and computation.

Many participants will also be new to calculations of this kind and unfamiliar to calculators, resulting in hesitancy and/or reluctance to participate in the process. However, in such situations, allay their fears by explaining to them that calculators are just like mobile phones, electronic tools used to compute numbers through various mathematical functions such as addition, subtraction, division, multiplication, and percentage. They are helpful tools in data analysis and hence there is nothing to be afraid of them. We needed to make friends with them and get over our fear. Ensure that all the participants get a chance to play with a calculator and do simple calculations on it. Encourage them to continue even after making a mistake.

Activity

Once they have finished calculating the percentages, ask the participants to think about how they can show their tabulations pictorially. Do not give them examples of bar graphs or pie charts, as many participants will have seen them before and will try to make diagrams according to them. However, some participants will also be creative enough to represent the data through other drawings – of trees of varying heights, flowers with different numbers of petals, and faces with various expressions. Encourage such creative expression by praising the drawings made by the participants. Ask the group facilitators to help represent the data frequencies accurately in the diagrams.

Once the participants have finished the tables as well as the graphs, ask them to display their work on the walls. Call the participants together for a 'gallery walk' – they can go around the halls and look at each other's tabulations and drawings.

Critical thinking is an important aspect of action research. Critical thinking is the opposite of regular, everyday thinking. It enables us to look at the world around us in a deliberate, systematic, and logical way and develop a deeper understanding of it. It further pushes us to question our own assumptions and become more reflective and evaluative when we process information. As action-researchers researching in our contexts, it is vital to employ critical thinking so that we can question, challenge, and change the world as we know it.

The following exercises help in orienting participants to the concept and process of critical thinking. However, it is important to note that critical thinking is a continuous process that cannot be taught in a day. It needs to be constantly reiterated throughout the research process – we need to 'tune' our thinking to be able to not take anything at face value, ask questions, seek new perspectives. Some notes at the end of the session give more information about ways we can think more critically.

Activity

This is an exercise that is designed to stimulate the critical thinking and analytical capacities of the participants. It can be based on any question or premise, e.g. ‘Parents/elders must use physical punishment as a way to discipline children.’ Ask the participants to divide themselves into two groups, those who agree and those who disagree with this statement. Each participant in the two groups gets a chance to voice their opinion. Each group has to convince the other group to change their mind. Individuals within the groups are free to move to the other group or form their group. Ultimately, the group with more numbers wins.

Sometimes, the groups may split into smaller groups within the Agree/Disagree positions. Encourage this by probing the participants to think of nuances within the two positions. For example, ask the participants in the 'Agree' group what they think about using physical punishment (beating/violence) on adults as well as children, for the sake of discipline. Those who think violence should be used on adults can form another group from those who think it should only be used on children.

After 15 minutes, end the debate and ask the participants to sit in a circle together for the plenary.

Discussion points:

Ask the participants to talk about their feelings during the debate and share their reflections. Specifically address those who changed their groups – why did they do so? After the participants have shared their reflections, summarise the debate by making the following points:

- According to each circumstance, we think and decide a 'place' for us, a stand we are going to take. But do we think about and question our beliefs, after listening to others?

- Just as there are other power differentials in society (gender/caste/race/money), is age also a power differential? We give less power to younger people, whereas elders are given more power, more authority, and control. But does that mean they have a right to dominate over those younger than them?

- In this debate, we reflected on our position, examined it, and understood how our experience helps us develop and strengthen this position. But we also listened to people located at positions different from us! It is not easy, and hardly ever possible, to get everyone to think alike, to get into the same position. Because we all have different experiences. But just as we have different points of view, we need to be critical, not only of others but ourselves as well.

- We need to develop critical thinking – the capacity to deconstruct opinions to understand where they are coming from. This ability to think critically is an important part of the research. We need to critically investigate everything we know, everything people tell us as 'facts'.

- Research is about asking questions and endeavouring to find answers. And its main component is analytical (or critical) thinking. The Analysis gives meaning to raw numbers.

- The reason we are different from nature is that we can ask questions, we can reason, rationalise. This capacity to think analytically is not only important in research but is essential to every aspect of our lives.

- Critical thinking helps us improve our questions. When our questions become more refined, we get better information. The more questions we ask, the more information we can glean.

- Critical thinking also means questioning the 'givens', asking why. Today, we live in a world of 'fake news'. Many vested interests are provoking young people into forming extremist opinions. Young people who get easily swayed by these thoughts are not equipped with the skills of critical thinking. They lack the analytical skills to challenge, resist extremist thinking because they don't think about them critically enough. If we think about it critically, we realise that such hate-mongering towards those who are different from us is not going to benefit young people. Rather, it is a ploy by those in power to acquire and maintain political power.

- Critical thinking enables us to transform ourselves, our lives.

Ways to think more critically:

- Ask Basic Questions: Some key questions you can ask when approaching any problem:

1. What do you already know?

2. How do you know that?

3. What are you trying to prove, disprove, demonstrated, critique, etc.?

4. What are you overlooking? - Question Basic Assumptions: Some of the greatest innovators in human history were those who simply looked up for a moment and wondered if one of everyone's general assumptions was wrong. From Newton to Einstein to Gandhi, questioning assumptions is where innovation happens.

- Be Aware of Your Mental Processes: A critical thinker is aware of their cognitive biases and personal prejudices and how they influence seemingly "objective" decisions and solutions. All of us have biases in our thinking. Becoming aware of them is what makes critical thinking possible.

- Evaluate the Existing Evidence: When you're trying to solve a problem, it's always helpful to look at other work that has been done in the same area. There's no reason to start solving a problem from scratch when someone has already laid the groundwork. It's important, however, to evaluate this information critically, or else you can easily reach the wrong conclusion. Ask the following questions of any evidence you encounter:

1. Who gathered this evidence?

2. How did they gather it?

3. Why?

Activity

After explaining the concept of critical thinking to the participants, ask them to sit in small groups according to the month they are born in (Jan-April, May-August, September-December) and ask them to discuss the following questions:

- Why should I develop analytical/critical thinking?

- How will it benefit my education, my work, my family relationships, and other aspects of my life?

- What capacities do I need to develop to become more critical?

Each group, after 10 minutes of discussion, comes to the front and presents their responses to everyone.

Activity

Show the following photograph to the participants:

Photo 1: Visibly impoverished girl and boy looking through a wire fence, at a group of uniformed, well-dressed students in a school ground.

Invite the participants to think about what the photograph is trying to convey. Participants will usually talk about the differences between the poor kids and the school kids. One big difference is which side of the fence they are on. After a few participants have spoken, ask them to reflect on another question:

What if the fence was not there, would there still be a difference between the two groups of kids?

Further, enquire if the participants think there are other such 'fences' or boundaries in our society that divide people and create hierarchies. What are some of these fences?

- Restrictions on girls – of time, mobility, association, clothes (Gender/Patriarchy)

- Untouchability and regarding some groups as 'lesser' than others (Race/Caste)

- Divide between educated and uneducated (Education)

- Rich and poor– can be distinguished by clothes, material possessions, English education (Class)

- Religion – those who are more in number have more opportunities. Minorities are stigmatised, harassed, and discriminated.

After talking about the various 'fences' or divisions in society, continue the discussion by asking the participants if they think these differences are natural or man-made. And if they are man-made, can we not un-make them? Is it possible to envision a society with no divisions or fences? How will that society look like? Ask a few participants to share their vision of an egalitarian society.

Also talk about how, just by looking at a single photograph, you can learn about social divisions and hierarchies. In this way, everything around us has another layer, a deeper meaning than what is seen on the surface. If we use the lens of critical thinking, if we ask the right questions, we can unearth this layer of meaning. And that is the first step towards the change that we want to see, towards the society that we have envisioned.

Activity

Taking forward this new lens of critical thinking, invite the participants to put it into practice by critically analysing the maps they have created of their communities. Connect the map analysis to the earlier exercise of photo analysis and ask the participant groups to present their maps in the following way:

- Explain the geographic features given in the map – the roads, the houses, the wells, the fields, etc.

- Identify what other boundaries are visible in the map – what we can call 'social boundaries' or social inequality. It could be related to which homes are in the centre and who live on the margins, and which communities are ghettoed. It could also be about which areas are safe and unsafe for girls and women. Are there any more social inequalities that can be analysed?

Give 10 minutes to each group to re-look at their maps and write a small analytical note for their presentation. Afterwards, when each group presents, encourage the others to ask questions to the presenting group based on their notes.

Discussion points:

After all the groups have presented, ask them to discuss the common features in all the community maps. Which particular social issue do they highlight? Is this issue also visible in the data that we have collected through other research methods?

Invite the participants to the final step of data analysis.

Activity

Now that the participants have finished a preliminary analysis of data and gained skills of critical thinking and analysis, invite them to an in-depth exercise of data analysis. We need to dig deeper into the data we have collected and organised, and bring out the truth it is trying to tell us! Sometimes, this truth leads us to more questions, which in turn propagates more research!

Explain the final step of data analysis to the participants. In this step, we review the collected data through a critical lens, and try to understand its meaning according to the objectives of our action research. In this process, critical thinking is our 'third eye' that enables us to ask two very important questions:

WHY: Why is something the way it is? and

WHY NOT: what is it that cannot be seen, but needs to be there?

Ask the participants to review their frequency tables, diagrams, explanations, and map analyses. Explain to the participants that this data has come from many sources – census, survey, village mapping, and the participants’ experiences and thinking. Depending on the thematic focus of the action research, ask the participants to write small 'essays' on different themes, citing the data collected as well as their own lived experiences. For example, if the themes in the action research are access to education, livelihood aspirations, survival struggles, and individual empowerment, then ask the participants to write an essay about each theme. The group of participants should discuss and write the essay together. Group facilitators can help in this process.

Some guide questions which can be used to stimulate the writing process are:

- What is any new information that was revealed by the data?

- What was something you had experienced and was validated by the data?

- Why do you think a particular trend is shown in the data?

- Do you think a particular trend shown by the data is good/beneficial for youth?

- What can be done to change/improve this trend?

- What actions can you take at an individual level to bring about change?

- What actions can you think of at the community level to bring about change?

Once the participants have finished writing their analytical essays, ask each group to read out one essay, which can be discussed in the big group. Focus on the actions, and discuss how participants can take actions at the individual and community levels.

In some cases, the participants or facilitators will realise that the data collected is not enough to fulfil the objectives of the research, or that the findings from the data require additional data to support it. In action research, this is completely acceptable, even encouraged. If this happens, discuss with the participants and plan a further round of data collection.

As a conclusion, everyone has to agree upon 2 individual and 2 community actions. Create a plan of action as well as deadlines for the proposed actions.

For the concluding session, ask the participants to recap everything they have done in the workshop. Prompt the participants if they forget anything. The participants should recount the following:

- Compiled the data from their surveys into a master sheet

- Made frequency tables and graphs based on the data

- Learned how to think critically

- Presented and analysed the village maps

- Analysed the frequency tables and wrote analytical essays

Congratulate the participants on putting their efforts and hard work into a successful data analysis, and that it was due to their perseverance that we were able to complete the analysis in a short duration of time. Further, ask the participants to share their experiences of the workshop, focussing on new skills or knowledge that they have acquired over its duration.

Finally, remind the participants to undertake the proposed actions in their communities once they go back.

WORKSHOP 3 – REPORT WRITING

- To provide report writing and documentation skills to the participants

- To provide the participants a space to reflect on the process and various steps of the action research

- To create community reports documenting the research findings, recommendations and actions

This workshop is of a shorter duration than the other core workshops. It can be one or two days long. In this workshop, the participants are expected to document their experiences of the action research and summarize the key findings of the action research in the style of a research report. The format of the report is given below. Notes are provided in each section for facilitators to guide the participants in the writing process.

- Need to be written by the organisation

2. Who are we? Profile of the participants- Ask the participants to think of creative ways to write this. They can draw caricatures, write poems for each other, or introduce themselves using funny memes

3. Our group – How did we come together? What is the spirit of our group? What is our identity in the village?- Ask the participants to write about what is special about their group. How do they work together? How do they help each other out? Do people recognize them as a 'researcher group' in the community?

4. Our community- Ask the participants to write about their communities. How do they see their community? What are its special features? Give them notes from the 'Community context' session in the first workshop

5. Joining the YARHow did the participants get introduced to the YAR? What motivated them to join it? What's the story behind it? Ask the participants to discuss and write

1. Coming together - Orientation meeting in the community

- Ask the participants to reflect on what happened in the orientation meetings in community. What were their initial reactions when they heard about the action research? Did they feel excited or nervous? Did they think they could do it?

2. Learning together - Workshop on introduction to research

- How did they participate in the first workshop? What was the first workshop about? What new things did they learn in this workshop? What was unexpected/ shocking? Did they have to get out of their comfort zone?

- Share the first workshop's photos and documentation with the participants to stimulate their memories

3. Action research methods

- What tools did the participants design for the YAR? Why did they choose these tools?

4. Research work in the field

- How did the participants carry out the data collection? What was the sample size? How did they use the research tools?

- Was it easy or difficult? How did they overcome the challenges? What did they learn in the process? Each participant can share one learning experience or challenge they overcame.

5. Community map

- Ask the participants to write about the process of drawing the community map, the learnings and challenges

6. Any actions taken while collecting data?

- Did any spontaneous actions emerge during the data collection? Write about those

7. Modules on gender, leadership, theatre, etc.

- Ask the participants to write about their experiences in the modules. What was the content? What were some new concepts or skills they learned? Did they have any striking realizations in this workshop? How did the participants connect the content of these modules to their lives? What was the most memorable moment in the modules? Have these modules inspired them to change any aspect of their personal lives?

- Share photos and documentation with the participants to stimulate their memories

8. Workshop on analysis

- What was the purpose of the data analysis workshop? What was the content of the workshop? What was the participants' reaction to seeing the data? How did they find the process of data compilation and counting, of using calculators for the first time? What were the new learnings and perspectives they gained? What were the major challenges during the workshop? Which data shocked/surprised you?

- Share the second workshop's photos and documentation with the participants to stimulate their memories

1. Analysis of data

- Ask the participants to edit and improve their theme-wise analysis written in the data analysis workshop

- Add the frequency tables and graphs which the participants feel are important

2. Key findings and major issues

- Ask the participants to draw key findings from the data analysis, as well as the major issues they have identified. These can be based on findings as well as lived experiences

3. Analysis of Map

- Ask the participants to edit and improve their map analysis written in the data analysis workshop

1. Theme wise recommendations

- Ask the participants to make a charter of recommendations. These need to be specifically addressed to various stakeholders with clearly specified demands.

Actions (Ongoing and upcoming) - Ask the participants to document any actions they have done in the course of the action research. These should be written like a story – what was the motivation behind this action? Did it emerge from the data? How did they plan and execute this action? Were there any challenges? How were the challenges overcome?

1. Learnings

- What were three significant learnings for the participant group, from this action research?

2. Challenges

- What were some of the major challenges? What didn't work? How did they overcome hurdles – individually as well as in a group?

3. Empowerment

- What was each participant's moment of change? Did the action research lead to any change in their identity in the community? Did it increase their participation in the community as well as in the family?

Participants can record their discussions and transcribe them later.

MODULE 1 – ON GENDER

Women and girls are disenfranchised, discriminated against, and face violence in many aspects of their lives. Society treats women as inferior or secondary beings, the ramifications of which can be seen on a variety of social structures. Being a girl in today's world has become increasingly difficult, with rising cases of gender-based violence which creates an environment of fear and increased restrictions on the mobility of girls. In order to combat this structural devaluation and disenfranchisement of women, we need to first understand its root causes. In order to do this, we need a critical lens to look at our society, our own lives, in order to examine the structural undercurrents that shape our worlds. We need to question our assumptions, challenge accepted norms, and even rethink our understanding of 'normal'. Along with developing an understanding of patriarchy and how it operates in our lives, we also need to develop and share strategies we can use to challenge and combat it.

This module meant to introduce the concepts of gender and patriarchy to the participants, understand how patriarchy operates through various institutions in society leading to disenfranchisement of women and girls, understand the patriarchal nature of violence against women and girls, and finally equip them with the skills to effectively negotiate with and challenge these manifestations of patriarchy in their lives.

By the end of this module, participants will be able to:

- Understand the difference between the concepts of sex and gender

- Become aware of discrimination based on gender; learn to recognise it in their own lives

- Become aware of patriarchy as the systemic root of gender inequality and its impact on our lives, and recognise equality as the opposite of/solution to patriarchy

- Discover and share strategies of negotiating with and challenging patriarchy in one's personal life

- Deepen understanding of gender-based violence as an effect of a patriarchal society

- Discover and share strategies of combating gender-based violence

- The two-day module is comprised of perspective building sessions that enable the participants to think critically about their experiences of discrimination and violence, as well as psycho-emotive sessions that buildtheir capacities and resilience to combat such experiences.

- The combination of cognitive and psycho-emotive inputs is necessaryto bring a holistic change in the participants' knowledge, attitudes and behaviours in a restrictive and patriarchal society.

- The module aims to become a space of 'cognitive liberation' for the participants where they can question their assumptions and become aware of newer possibilities of living and relating.

- The sessions should not only free the participants from the mental shackles of expectations and stereotypes and 'should be's, but also enhance their emotional capacities to contend with patriarchal and violent forces in their daily lives.

- This can happen only whenemphasisis given to dialogue and sharing between the participants, especially personal stories of successful negotiation and challenging of norms and restrictions.

Activity

Sociogram is an ice-breaker which aims to visually map differences within a group. This activity is fun to do and makes the participants think and take a stand on questions posed to them. To begin, create a list of questions to ask the group. These may range from personal likes and dislikes, beliefs, family information, along with questions related to gender. Some example questions are:

1. How many of you like dancing?

2. How many of you are pursuing a hobby apart from study?

3. How many want to study beyond graduation?

4. How many can cook?

5. In how many people's homes the men in the family do housework?

6. How many of you can drive a motorbike?

7. How many do fasts?

8. How many have working mothers?

9. How many can wear the clothes they want?

10. How many roam about alone after dark?

Every time a question is asked, the participants have to take a step forward if their answer is yes. Then the numbers of 'yes' and 'no' can be counted. Then write the question along with the number of participants saying yes and no, thus mapping how majority of people think and behave. This activity also helps to break the monotony and have some fun with the participants. In this module, the Sociogram activity can be focused on gender differences.